disputed the notion that hypervisors are a commodity. "I will happily tell you why vSphere is the best product," said Gelsinger. "It's the best hypervisor. It has features, like DRS [dynamic resource scheduler] and HA [high availability] and so on that aren't replicated in any of the KVMs or Hyper-Vs or anything else."

Gelsinger also emphasized VMware's work beyond the hypervisor -- including integrating OpenStack into predominantly vSphere environments. "We are adding support for the OpenStack compute resource Nova APIs to vSphere for management and vCAC [vCloud Automation Center] at the provisioning level," he said. "We can provision into the OpenStack consumption APIs as well."

VMware's work with OpenStack acknowledges that IT wants the flexibility of a multi-cloud environment. "We're embracing [OpenStack] APIs at multiple levels of our products and saying we will increasingly support these open interfaces," said Gelsinger.

In fact, at this year's VMworld, the company delivered on that promise by releasing its own OpenStack distribution for use within vCenter; see a summary of the announcement here. VMware executives cited cloud developer's preference for OpenStack's open, extensible API as motivation.

The strategy of building a cloud platform from proprietary components while supporting enough open APIs to peacefully coexist with OpenStack in a multicloud data center makes sense, but it's primarily a defensive maneuver to prevent defections as companies build native cloud applications -- and the infrastructure to support them.

VMware brings a $1 billion-plus annual R&D budget to this competition, but open source advocates are undeterred. They say there's plenty of corporate money behind open projects and point out that most public cloud services are built on a foundation of open source software -- even if, in the case of Amazon and Google, they don't run OpenStack per se. OpenStack proponents also note broad industry support for the project, with more than $10 million in funding from eight platinum members and 19 gold members that each pledge $500,000 and $200,000, respectively, to the OpenStack Foundation annually.

In talking about open source innovation in cloud software, specifically hot new projects like Docker (application containerization) and Mesosphere (pan-data center resource aggregation and administration), Red Hat's Whitehurst puts it bluntly: "There's a ton of cool stuff going on, but that's only happening with Web 2.0 companies, and it's all happening in open source." Whitehurst echoes early evangelists, saying that open source is a superior and scalable model for innovation when users, developers, and vendors are all involved in defining and solving software problems.

The big winner in this skirmish is IT.

Key benefits from open source cloud stacks are better interoperability and lowered risk of vendor lock-in. Indeed, vendors themselves often cite these reasons for supporting open source projects. Case in point: IBM's announcement of premier-level sponsorship for OpenStack. IBM believes that "fostering an industry-wide, open cloud architecture and simplifying how applications are built and deployed" will drive broader cloud adoption, writes Angel Diaz, IBM's VP of Open Technology and Cloud Performance Solutions. IBM sponsors OpenStack as part of its active role in "driving widespread adoption of cloud technologies based on open standards to enable interoperability and avoid vendor lock-in."

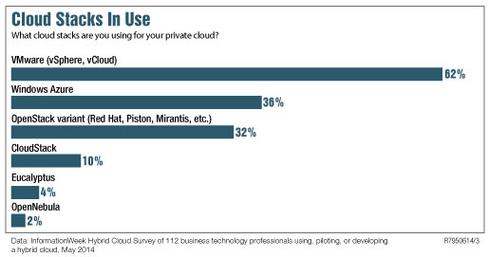

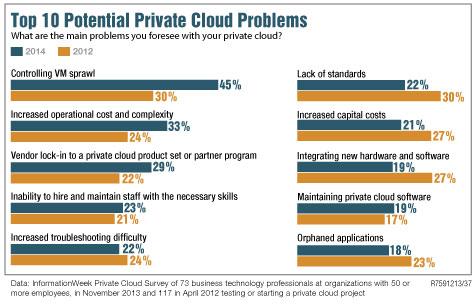

IT is getting more concerned about lock-in. While only 29% of respondents to our Private Cloud Survey cite vendor lock-in as one of the main implementation problems they anticipate, that's up seven points since 2012. Standards are particularly important when building a hybrid cloud mixing public and private services. Of those responding to the InformationWeek Hybrid Cloud Survey using, piloting, or developing a private cloud, 62% have or are building the ability to move applications and data between public and private clouds. However, while their internal cloud is most likely to be based on VMware, externally they more often use Microsoft Azure or AWS. Although this doesn't augur well for OpenStack (or vCloud Hybrid Service, for that matter) it does reinforce the need to address lock in and multicloud integration and management (a topic we cover in depth in this report).

Whitehurst told us that one way companies are hedging their open vs. proprietary cloud bets is by building a parallel greenfield infrastructure for new, cloud-optimized applications. "If you look at cloud as an incremental baby step from your existing application in a virtual environment with a few more management tools, it probably doesn't make sense to rethink your infrastructure," he says. "But if you look at where most new applications are getting built, they're happening in an open infrastructure." Although Whitehurst does see companies improving existing virtualization systems for legacy (largely Windows-based) applications, he says they draw a distinction between these and what might be called "native cloud" applications.

Gelsinger would counter that OpenStack is more of an open cloud framework than product, and indeed, VMware's OpenStack distribution bolsters that viewpoint in that it can include both open source and closed source products. VMware's cloud management platform does likewise and will increase its support of open APIs. In other words, "we're open, too.'"

Bottom line: The zest with which big vendors are scrambling to embrace OpenStack confirms that it will become the lingua franca of clouds, defining the interfaces and APIs that allow different cloud systems, whether proprietary like AWS and vCloud or open source like Mirantis, Piston, and Red Hat OpenStack, to interoperate. That doesn't mean, however, that enterprises will use pure OpenStack.

Software-defined networks

If cloud stacks are the front line in the open source/proprietary software battle, SDN is the left flank. Once again, VMware is a key participant. However, the definition of "SDN" is