Contention between open source groups freely releasing code and commercial vendors capitalizing on proprietary products started the minute software became a profit-generating industry. The latest battleground? Enterprise data centers, with fights focused on cloud stacks, software-controlled networks, and big data systems. The lines are far from clear-cut. Established IT vendors incorporate open source code, APIs, and standards in their products. Startup companies are happy to commercialize public open source projects if they see demand. IT must take a pragmatic approach to software and vendor selection.

It's business, not dogma.

Unfortunately, human (and especially, engineer) nature being what it is, debates tend to take on a moralistic -- and occasionally anti-capitalist -- tenor, conflating open source software with idealized notions of liberty, community, and creative license. The tone was set early on by open source evangelist Richard Stallman, father of the Emacs editor and many other OS subsystems that were eventually subsumed by Linux. From Stallman's Gnu Manifesto:

"I consider that the Golden Rule requires that if I like a program I must share it with other people who like it. Software sellers want to divide the users and conquer them, making each user agree not to share with others. I refuse to break solidarity with other users in this way. I cannot in good conscience sign a nondisclosure agreement or a software license agreement."

There are also cold, hard business and technical reasons why an open source development model makes sense, articulated by that other famous philosopher of the movement, Eric Raymond. Chief among them: software quality, security, reliability, and speed of development. In Raymond's view, open source replaces Brook's Law, which holds that adding manpower to a late software project makes it later, with Linus's Law: "Given enough eyeballs, all bugs are shallow."

Software vendors counter that without proprietary software and intellectual property protections, there's little incentive to invest and innovate. Both sides make valid points, and the fact is, open source projects like OpenStack, Open Daylight, Hadoop, and even core operating systems such as Linux and Android have been adopted and are funded by large IT vendors.

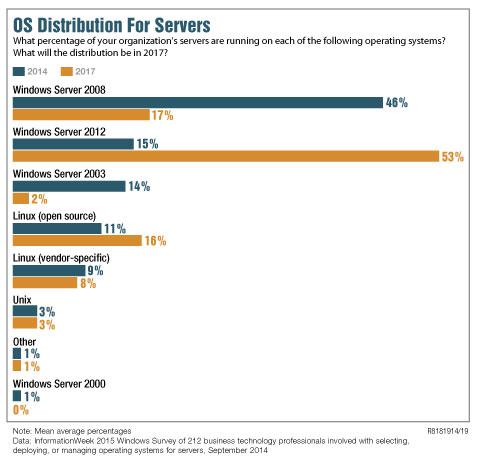

Windows versus Linux is the longest-running skirmish between open source and proprietary software. It's also now largely moot. As virtual machines become the default application environment -- and our latest InformationWeek State of the Data Center Survey finds 64% of respondents will have half or more of their production servers virtualized by the end of 2015 -- the underlying guest OS doesn't much matter. But as one area of contention subsides, many more arise. Technologies such as private cloud stacks (OpenStack, vCloud) and application containerization on low-power, non-x86 systems could shift the server balance. Open source software is making headway in three critical areas important to people running enterprise data centers: cloud stacks, software-defined networks, and big data platforms.

Let's look at each.

Cloud stacks: VMware still the default

Cloud stacks are perhaps the most visible software category in the data center for which open source presents a viable challenge to proprietary systems. Red Hat CEO Jim Whitehurst rightly characterizes the cloud as a disruptive force. "And in those paradigm shifts, generally new winners emerge," says Whitehurst. If Red Hat and other advocates have their way, OpenStack will be the standard cloud platform for service providers and enterprises alike.

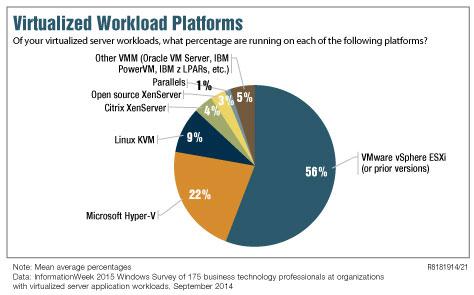

Despite abundant media hype, however, OpenStack faces an uphill battle. VMware is the de facto virtualization standard for almost two-thirds of enterprise IT organizations, and the company is building on that foundation. Although VMware faces competition on two fronts -- Microsoft Azure (proprietary) and OpenStack (open source) -- make no mistake, within the enterprise, it's still a David vs. Goliath situation.

A recent InformationWeek survey of those using, piloting, or developing a hybrid cloud found OpenStack trailing VMware by 30 points. Although OpenStack has made progress, with nearly one-third of respondents using an OpenStack variant, its penetration remains almost identical to Azure's. Results from our 2014 Private Cloud Survey are less kind to the open source cloud stack. While 65% of respondents use VMware as part of their cloud designs, only 18% check in with Red Hat, and a mere 7% use OpenStack.

The data isn't surprising when you consider that, for many enterprises, a private cloud featuring such niceties as self-service provisioning and automated workload migration is an extension of the existing virtual server infrastructure -- over which VMware has held sway since effectively creating the software category (at least on x86 platforms) a decade ago. And VMware isn't sitting still. The company is aggressively developing its own cloud stack replete with virtual networking and storage, infrastructure automation, workload orchestration, and public-private cloud integration. In fact, in an exclusive interview after his Interop keynote, CEO Pat Gelsinger