Three months ago, my wife and I moved to a new apartment in Barcelona. A week after our telephone line and DSL service were installed, our ISP offered us fiber-to-the-home (FTTH) service without additional cost. We didn't think twice and are now enjoying a very high-speed connection, high-definition Skype calls, music and video that stream smoothly, and the ability to have several devices connected simultaneously without any service degradation.

Having some type of fiber or high-speed cable connectivity is normal for many of us, but in most developing countries of the world and many areas of Europe, the US, and other developed countries, access to "super-fast" broadband networks is still a dream.

This is creating another "digital divide." Not having the virtually unlimited bandwidth of all-fiber networks means that, for these populations, many activities are simply not possible. For example, broadband provided over all-fiber networks brings education, healthcare, and other social goods into the home through immersive, innovative applications and services that are impossible without it.

Recently, both the US Federal Communications Commission and Ofcom (the British telecom regulator) have been trying to raise the minimum speed that can be offered as "broadband" in order to meet the current demand for speed that today's applications require. In the US, ISPs can sell 4 Mbit/s as broadband, while Ofcon defines anything over 2 Mbit/s as broadband and over 25 Mbit/s as super-fast broadband.

Verizon and AT&T are fighting the FCC's proposed 10 Mbit/s broadband minimum speed, claiming that most customers don't need such fast connections. But the reality is quite different. Most broadband users have several devices (laptops, smartphones, tablets, game consoles, smart TVs). The bandwidth delivered by DSL -- or even cable -- is not enough for heavy users.

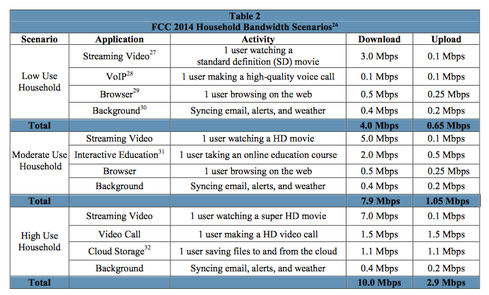

According to the FCC (chart below), the typical "High Use Household" requires a 10 Mbit/s downlink and 3 Mbit/s uplink -- figures I believe are very conservative. To me, a 30 Mbit/s downlink connection is the minimum you need today in a household with around 10 devices.

The European Union Digital Agenda target is to have 50% of homes served by Internet speeds of at least 100 Mbit/s by 2020.

Alternatives to fiber, such as cable (DOCSIS 3.0), are not enough, and they could be more expensive in the long run. The maximum speed a DOCSIS modem can achieve is 171/122 Mbit/s (using four channels), just a fraction the 273 Gbit/s (per channel) already reached on fiber.

FTTH connections are currently booming in countries such as Portugal and Spain. In Spain, Telefónica will reach 10 million households this year. Jazztel, recently acquired by the French operator Orange, will reach 3 million more users at the end of the year. Portugal's main operator, Portugal Telecom (PT), had more than 1.3 million homes connected at the end of 2013, with plans to reach 2.5 million this year.

The advantages of deploying FTTH in Europe include the higher population density and the fact that most people live in apartment buildings, making the ISP's investment much smaller per user. According to numbers released by Jazztel in Spain, the cost of switching a user to FTTH is about €220 ($280), provided that the city has a "black fiber" infrastructure in place. Conversely, due to the large suburban population, the cost of delivering FTTH to a US household is close to $2,200.

That is why US ISPs need to cooperate to deploy fiber. Sharing the cost of the basic infrastructure (dark fiber) could bring the technology to areas being left out today. Once the basic "network" is in place, the ISPs can use cheaper "last-mile" solutions such as fiber-to-the-cabinet (FTTC) and coaxial cable to connect remote customers.

The digital divide is much bigger in developing countries, where few have any fiber network, and there are no plans to deploy fiber at all. Many countries are counting on wireless networks, such as LTE and WiMax, to solve their broadband problems, but that will leave most of their citizens without reliable, cost-effective fast broadband connections.

Meanwhile, the amount of data being transmitted is increasing exponentially. According to Ofcom, UK Internet users sent or received more than 650 petabytes of data over fixed lines in June -- an increase of 26% over the same month last year -- and the numbers keep growing. In order to accommodate the demand, deploying all-fiber networks is a must, not a luxury.

One advantage of all-fiber networks is their ability to scale to faster speeds simply by upgrading the modulating electronics. This way, all-fiber networks can keep up with the demand of new applications and the increasing number of devices connected to the grid.

In order to solve the new digital divide of the 21st century, governments and industry leaders need to create the framework to deploy fiber connections to reach a broader swath of the world's population. The rapid increase in bandwidth requirements and the growing number of devices in use could leave many communities behind if their communications infrastructure is not improved soon.