Whether you’re a startup trying to disrupt a market or a stalwart attempting to gain ground on your competitors, business is increasingly about innovation. Software, it turns out, is soft and companies are embracing this malleability to find innovation.

Need proof that companies in all verticals are embracing this? Pick any company and do this Google search: <company name> software developer jobs. When I did this recently, I found that consumer goods giant Proctor & Gamble has more than 40 job openings for software developers. Wal-Mart, which sells the products, has more than 90, and Ford more than 60. None of these companies are based in Silicon Valley or generally thought of as technology leaders, but these days, every company is a software company.

If you’re going to spend all that money on a software development staff, what techniques would increase the odds that they find the innovation management is so desperately after?

Most modern application development tuned to innovation discovery is based on Kubernetes, the open source container clustering technology. Why? A microservices-based application architecture running on Kubernetes maximizes the number of iterations a team of developers can churn out in a year.

Most ideas fail

The best way to understand why maximizing the number of iterations on software is the driving factor for innovation is to examine the venture capital (VC) market. After all, VC investors are looking to find disruptive technologies that can change industries, typically through innovation. CB Insights analyzed VC returns and found the following:

“Of the 1,098 tech companies we tracked that raised seed rounds in the US in 2008-2010, less than half, 46%, managed to raise a second round of funding. Every round fewer companies advance toward new infusions of capital and (hopefully) larger outcomes. Only 14% of our companies went on to raise a fourth round of funding, which typically corresponds to a Series C round.”

Put another way, most ideas fail.

How do VCs compensate for this daunting win percentage? By placing a lot of much smaller bets, according to this Venture Beat report. If only 14% of your investments pan out, it’s better to place 200 bets than it is 10. In other words, the more iterations you can get out of the system the better your chances are at finding a single innovation.

Microservices equals more iterations

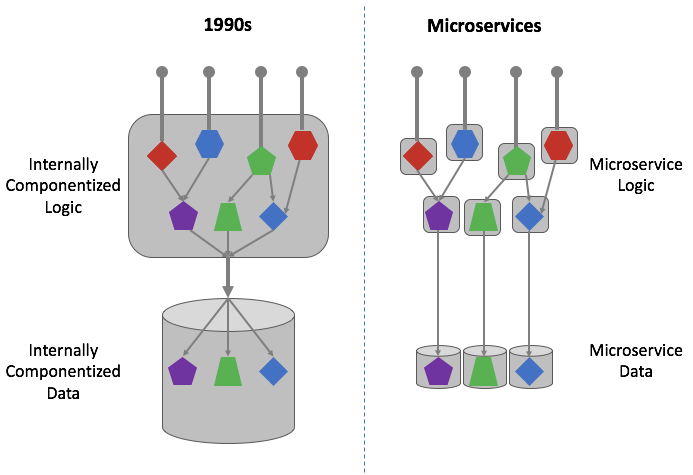

How do you design software and deployment processes in such a way that maximizes the number of iterations, and therefore your chances at innovation discovery? As client-server software architectures emerged in the 1990s, applications typically were separated into business logic and data components.

Each tier might have further internal components that interact with each other, but at that time the entire application was written in one language, existed in one memory space, and had to be deployed together for fear of interfering with the internal dependencies. This complexity led to, at best, quarterly releases which meant that you had only four chances each year to find an innovative feature.

Over the last 25 years, a different software architectural approach has evolved that separates the internal components into microservices. Each much smaller component presents an API to other components and as long as that API doesn’t change, the internal workings of the microservice can be written in any language and deployed independently of other components.

The path to Kubernetes

Monolithic architectures and quarterly releases were acceptable in the 1990s in large part because the deployment targets were bare-metal servers in private corporate data centers. IT’s focus was getting the most out of the capex of the physical hardware and each release introduced risk that might bring a server down.

But when virtual machines (VMs) came available in the late 1990s, the compute resources on top of which software ran could be replaced in 10 to15 minutes instead of three months. Containers evolved from VMs using a different resource separation technique to provide a compute shell on top of which software could be installed in seconds instead of minutes. This led to smaller pieces of logic, microservices, which could be upgraded independently of one another.

But the crossroads a microservices architecture finds itself is the need to run at scale with lots of containers running across multiple logical or physical hosts that can all be managed from a single interface or “pane of glass.” This is exactly what Kubernetes provides IT administrators; the underlying compute layer can be organized efficiently and not cause deployment friction for the software development iteration process.

Simply put, Kubernetes is a means to an end. It supplies a reliable foundation for clusters of containers that can be published frequently, enabling the deployment process at the end of an iteration to occur more smoothly and rapidly. Kubernetes leads to more innovation because it removes barriers in the deployment process that typically slow down development iterations, and more iterations equals more innovation opportunities.